CASE PRESENTATION

Today is the first time that Carla1 will be working with clay during expressive art therapy.

It is natural clay, fine fireclay. Carla likes the feel of the clay on her hands, she kneads and pushes the piece into her hands enthusiastically. There is play and fun, an exploratory inner child part is addressed in this first session.

As the session progresses, Carla gets the idea that the piece of clay in her hands must become ‘something’. A well-defined idea emerges, with requirements for function and aesthetics. The space to play and experiment is now all of a sudden significantly reduced, by these self-imposed requirements. Carla’s arousal increases visibly when she undertakes attempt after attempt to give shape to the emerged idea.

In fact, at this point Carla is already caught in a trap: no matter what she will produce, it will never be good enough. This is the image that Carla has internalised of herself with a history of early childhood trauma; that she is no good and that everything that comes out of her hands is worthless. Every time the sculpture is finished and Carla judges it not quite good enough, she destroys the piece and starts over. A re-enactment of not being permitted, or not being able to be a child in the past, is being repeated in the here and now, with tremendous energy and tempo. After attempt four the therapist is able to intervene and directs the client to allow the current attempt to exist, as an experiment, and to investigate what happens when one deviates from the beaten, destructive path. The therapist moves the piece a little further away from Carla but still within sight, and she offers Carla a new piece of clay to accommodate the increased arousal.

The destructive force is directed to the new piece of clay and space is opened to allow the (perceived) failure and all that it represents to remain. Carla weeps, not for the failure of the sculpture, but due being allowed to feel the grief of that which was lost. The therapist stays close, acknowledging the emotions released and encouraging Carla with a sense of trust (I can witness it and you can bear it) to give the emotions space. A moment arises in which the pain and sorrow are allowed to exist.

1 Carla is a fictitious name. The case describes part of a session in the beginning phase of the visual art therapeutic process. After these experiences nothing is ‘finished’ or ‘solved’, but a change has occurred in dealing with one’s own feelings of pain, sadness, failure and worthlessness. An impetus for further investigation and work.

MATERIALS IN EXPRESSIVE ART THERAPY (2)

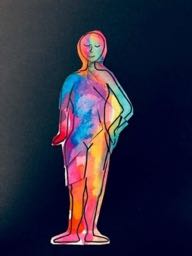

As the previous example shows, the visual medium also offers a very welcome safety net, in the case of increased or decreased arousal. This space offers to work with physically involved methods that ventilate, regulate, or activate and can more than once act as a lifeline during the session. It offers the client, and perhaps even the therapist, a opportunity to co- and self-regulate and, in that way, return to a more comfortable level of arousal, which allows continuation with the contact in the here and now in all its forms, contact with the inner experience, contact with the visual work, contact with the therapist, and contact with the environment, see figures 8 and 9. In this way, clients can continue working through their emotions.